Notification settings New notifications

Chinese Youth Who Risked It All to Film Uyghur Camps Gets Nabbed by ICE

News • ahmedla posted the article • 0 comments • 176 views • 2025-12-15 03:20

This is a story about guts, a getaway, and a cruel twist of irony.

In October 2020, Guan Heng, a young guy from Henan, China, drove solo deep into the heart of Xinjiang. Armed with a long-lens camera, he documented the internment facilities hidden behind the wilderness, towns, and military barracks. To get this footage out to the world, he embarked on a hair-raising escape: zigzagging through South America, and finally, piloting a small boat alone for 23 hours across the ocean, making landfall in Florida from the Bahamas. After arriving in the US in 2021, he released the videos as planned. These clips became key evidence for the international community—including the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News—to confirm what China was doing in Xinjiang.

Guan Heng thought he was safe. But four years later, he lost his freedom right here in the States. In August 2025, during an ICE raid targeting his housemates, Guan was arrested in Upstate New York for "illegal entry." Now, sitting in the Broome County Correctional Facility, he faces the threat of deportation—being forced back to the very country he risked everything to escape.

On the morning of August 21, 2025, in a residential neighborhood in Upstate New York, Guan Heng was jolted awake by a violent pounding on the door. It was ICE agents.

They weren't there for him. Their target was his roommate—a couple in the business of flipping shops who had been reported due to a financial dispute. But when the agents stormed in with a search warrant, they "bumped into" the 38-year-old Guan Heng, and he was taken into custody on the spot. The exchange went like this:

Agent: "How’d you get into the country?"

Guan: "I drove a boat over from the ocean myself."

Agent: "Do you have an I-94 form (arrival record)?"

Guan: "No."

Guan was first taken to an ICE office, then tossed in a county jail near Albany for a day. From there, he was shipped to an immigration detention center in Buffalo for nearly a week, before finally landing where he is now—Broome County Correctional Facility.

"They couldn't care less if I have a work permit or what the status of my asylum case is," Guan said, his voice thick with confusion and frustration during a phone interview with Human Rights in China in October 2025. "They only care about how I entered. They just say I didn't come through a normal customs checkpoint, so the act itself is illegal."

His pending asylum interview, his legal work permit, his New York State driver's license... in the eyes of ICE, all of it was worth zilch compared to the fact of his "Entry Without Inspection."

With the Trump administration cracking down hard on illegal immigration, the Broome County jail is packed to the gills. Months have passed, and Guan waits for the outcome of his case in a state of anxiety and depression. Nobody there knows what this young man from China went through over the past few years; nobody knows that the footage he risked his life to shoot provided crucial corroboration of the Chinese authorities' actions against the Uyghurs. And nobody knows the immense danger he faces if he gets sent back.

1. "I wanted to go to Xinjiang and see for myself what was really going on."

Guan Heng calls Nanyang, Henan his home. He was born in November 1987.

According to Guan and his mother, his parents divorced when he was young, and he was raised by his grandmother. After she passed, he’s been on his own. Before leaving China in July 2021, he worked a bunch of different gigs—ran a fast-food joint, worked in the oil fields for a few years, and later freelanced. By his own account, he learned how to "jump the Great Firewall" (bypass internet censorship) pretty early on.

Unlike many young Chinese people, Guan didn't just use the VPN to watch movies or listen to music. He used the internet to touch the "forbidden zones" buried by official narratives: from the Great Famine of the 1960s to the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989. This raw information from the outside world hit him hard, cracking his worldview wide open.

"I learned bit by bit, and finally realized that the Chinese government was hiding so many dirty secrets," he recalled in a jailhouse phone interview with the author in November 2025. He said that since graduating college, he had become a silent dissident—someone living under the regime, but whose mind had already "broken out of prison."

In 2019, Guan rode a motorcycle from Shanghai all the way to Xinjiang as an adventure tourist. He thought it would be a scenic road trip, but he slammed into an invisible wall of high-pressure control.

" The vibe was obvious," he said. "As soon as you enter Xinjiang, there are checkpoints everywhere, police and armed guards all over the place. Even checking into a hotel requires repeated registration and facial recognition." At gas stations, he faced strict restrictions just for being on a motorcycle. This trip gave him a firsthand look at the government's harsh social management system in the region, though he didn't fully understand the depth of it at the time.

In 2020, when COVID hit, Guan was locked down at home like hundreds of millions of other Chinese people. Bored out of his mind surfing the web, he clicked on a report from the famous American outlet BuzzFeed News (BFN). The report used satellite imagery and data to reveal a massive network of concentration camps spread across Xinjiang.

In that moment, the questions from his 2019 trip were answered. He realized those checkpoints, police, and facial recognition systems he saw were actually the outer perimeter of this massive surveillance state.

"Knowing the Chinese government, they love covering up stuff they don't want people to see," Guan said. "It really piqued my interest, especially since I'd been there and knew nothing about it. I immediately wanted to go back and see with my own eyes what the hell was going on."

He knew perfectly well that for a regular guy to do this as a tourist was basically a "suicide mission." "I fully expected the risks," he said calmly. He started prepping like he was planning a covert op: instead of his own pro gear, he rented a long-range DV camcorder online so he could film from a safe distance.

He prepped two SD cards. One for filming, which he’d hide in a secret spot in the car immediately after shooting; and a dummy card to stick back in the camera. "I was afraid of getting stopped and searched," he said. "At least they wouldn't know what I'd filmed."

In October 2020, Guan Heng drove alone toward the trouble spot he’d visited a year prior—Xinjiang.

2. "Roaming" Xinjiang for three days: Verifying prison coordinates one by one.

Guan's trip wasn't an aimless wander; it was a treasure hunt based on a map. That "map" consisted of satellite coordinates marked as suspected "detention camps" in the BuzzFeed News report.

He spent three whole days crisscrossing the vast lands of Xinjiang, fact-checking the coordinates marked as gray (low confidence), yellow (medium confidence), and red (high confidence).

His first stop was Hami City. Before hitting the city, he went to a place called "Beicun," marked with a gray tag. It was a pink building, no barbed wire, didn't look like anyone was there—didn't look like a prison.

Next, he drove into downtown Hami and found a yellow marker. The sign out front read "Hami Compulsory Drug Rehabilitation Center." It was in a busy area with heavy traffic, which made Guan skeptical. "A rehab center in a busy downtown isn't likely to be a detention camp." But right after that, he found another yellow marker—"Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps 13th Division Detention Center."

This place immediately put him on edge. It was tucked at the end of a small alley. Not only did the detention center itself have towering walls, but several adjacent courtyards were also ringed with high walls and barbed wire—definitely not normal residential compounds. This matched the description of the concentration camps perfectly.

To cover his tracks, Guan bought some snacks at a shop at the alley entrance on his way out and "deliberately" paid with WeChat. "If I got questioned," he explained later, "at least I’d have an excuse for why I was in that dead-end alley."

The second day, Guan was on the road constantly. He passed through three counties: Mulei, Jimsar, and Fukang. He found that many of the BFN markers pointed to existing "detention centers" or "jails"—Mulei County Detention Center, Jimsar County Detention Center, Fukang City Detention Center. In Mulei, he found two gray markers: a "Farmers and Herdsmen Training School" and a "Vocational Education Center." Although the buildings looked abandoned, the barbed wire still on the walls seemed to whisper of their former use.

That day's journey made him realize the scale of the campaign was far bigger than he imagined—the authorities weren't just building new facilities; they were utilizing, retrofitting, and expanding the entire existing incarceration system.

However, this was tricky. Watchtowers and barbed wire are standard for jails, so judging by appearance alone, it was hard to tell if they were being used as concentration camps for Uyghurs.

On the third day, Guan drove through three cities: Urumqi, Dabancheng, and Korla. This was his most productive—and most dangerous—day.

In the suburbs of Urumqi, following the coordinates, he found the "Urumqi No. 2 Education and Correction Bureau (Drug Rehab Center)." He parked far away, posed as a jogger out for a morning run, and filmed with a GoPro as he walked. He not only captured the rehab center but also discovered three other heavily guarded compounds nearby. At the gate of one facility, he filmed a vegetable truck unloading—proof the facility was active.

Right after, at a place nearby called "Gaoke Road," he made his key discovery. On one side of the road lay a sprawling complex of huge facilities, complete with high walls and watchtowers, yet it wasn't marked on any map. Guan zoomed in with his long lens and successfully captured the bold red characters on the roof: "Reform through Labor, Reform through Culture."

That afternoon, he headed to Dabancheng. This was a "red marker," hidden deep in the wilderness far from the highway, without even a gravel road leading to it. Guan parked by a pond and climbed a high dirt mound alone.

"I was nothing but nervous," he recalled. Lying flat on the mound, his lens filled with a brand-new, massive, but seemingly unopened facility. He snapped his shots and hurried down, breaking into a cold sweat—he realized there was actually a house on top of the hill he’d just climbed, and down by the pond where he parked, a fisherman had appeared out of nowhere.

Forcing himself to stay calm, he walked up to the guy. "Hey boss, catch anything?" After confirming the guy hadn't noticed his shady behavior, he got in his car and sped off.

The final stop was Korla, 339 kilometers from Urumqi. Here, the coordinates pointed behind a military base (there were tanks at the gate). It was a massive, heavily guarded facility, and the only way in was through the military camp.

As Guan tried to pull off onto the shoulder to get a shot, someone from a shop next to the base walked out and stared him down, dead in the eyes.

In the tension of the standoff, Guan thought fast. He slammed on the gas, drifting his high-chassis SUV in the dirt, spinning donuts, deliberately acting like a guy just testing out his car's performance. The "shopkeeper" seemed confused by this crazy driver, watched for a bit, and then boredly went back inside.

The second the guy turned around, Guan stopped, whipped out his long-lens DV, and captured the final scene of his video.

3. Drifting at sea for a day and a night: Smuggling into the US from the Bahamas.

The video was done. Guan Heng possessed a "digital bomb," but he quickly realized a fatal problem: he couldn't hit the "publish" button without blowing himself up.

"I knew, finishing the video was one thing, but once it hit the internet, the police would definitely find me," Guan said in the interview. "If they got to me, the videos would either never get out or be deleted, and my life would be in danger."

The only way out he could think of was to leave China first.

But the fuse on this bomb was stretched painfully long. Since the outbreak in 2020, China's borders had been sealed. Guan had nowhere to go, sitting on this footage in depression and anxiety. Finally, in the summer of 2021, a window opened. On July 4, he left via Shekou, departed from Hong Kong, and flew to Ecuador, a South American country that was visa-free for Chinese passports at the time.

He stayed in Ecuador for over two months for one reason: to get the Pfizer vaccine. He didn't trust the Chinese domestic vaccines, but the policy back home was getting stricter—"No vax meant a red health code, you couldn't go anywhere."

After two shots, he flew to another visa-free country—The Bahamas. Here, he was separated from his final destination by just a strip of water. He wanted to buy a boat from China and have it shipped to save money, but his Bahamian visa was ticking away—he recalls only having 14 days—and logistics were slow. By October 2021, he couldn't wait any longer. He spent his last $3,000 at a local marine supply store on a small inflatable boat and an outboard motor. He launched from Freeport, Bahamas, aiming for Florida. Google Maps said it was about 85 miles as the crow flies.

According to Guan, he had zero nautical experience, didn't know how to row, and got seasick easily. This was his first time "captaining" a vessel. His only tools were a mechanical compass and a phone with offline GPS maps.

"I was drifting on the ocean for nearly 23 hours," he recalled. He brought plenty of food and water, but was so nervous he "only drank one can of Coke the whole time." The biggest threat wasn't the waves, but his sketchy engine.

"I didn't have much money, so I didn't buy a closed fuel tank," he said. "I had to hold a gas can and pour fuel directly into the engine while the boat was rocking violently." Gasoline spilled everywhere, filling the dinghy with heavy fumes, ready to explode at the slightest spark.

"That boat turned into a floating bomb," Guan said. "I was actually terrified, because if it caught fire, I'd never make it to America."

He planned to land at night to avoid detection. But in the endless drifting, his only thought was "just get there."

The next morning, he saw the Florida coastline in the distance. Around 9 AM, the boat hit the sand. There were already tourists taking morning walks on the beach, and an elderly couple was walking toward him. Guan's heart was in his throat, terrified they would call the cops.

Ignoring the boat and his scattered luggage, he grabbed his most important backpack. The moment the boat hit the shallows, he jumped off and sprinted into the coastal bushes. Hiding in the brush, gasping for air, he watched a Coast Guard patrol boat cruise by just offshore. But he was safe.

Just like that, through smuggling, Guan Heng arrived in the "Free World" he had longed for.

4. The video shocks the web, but he and his family pay a heavy price.

According to Guan, before he launched from the Bahamas, he had already scheduled the video release. "I didn't know if I'd make it to the US alive," he said. "I couldn't wait until I arrived to publish." The video about the Xinjiang concentration camps finally went public on his YouTube channel on October 5, 2021.

The video immediately triggered a massive reaction. As rare, first-person footage from a Chinese citizen, Guan's video was quickly reported on and cited by media outlets like Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Asia. More importantly, it provided key on-the-ground proof for the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News. In interviews, BFN reporters emphasized the extraordinary value of Guan's footage, praising his courage and stating that the new information confirmed their analysis of what was happening in Xinjiang.

Meanwhile, as the one who lit the fuse, Guan himself faced pressure beyond his worst nightmares—a massive wave of attacks from Chinese state security and online propaganda trolls began immediately.

Shortly after the video dropped, a YouTuber named "Science Guy K-One Meter" posted a "doxxing" video, stripping Guan's personal info bare—real name, birthday, college, home address—everything. This "Science Guy," typically, posts pro-CCP content.

"They doxxed Guan Heng," said Ms. Luo, Guan's mother, in an interview with Human Rights in China on November 1, 2025. Her voice trembled with anger. "The comments underneath were incredibly nasty, calling him a traitor to the Han race, and saying things like 'hope he gets accidentally killed by a black brother in America'."

Simultaneously, a "siege" on his YouTube channel began. "First they reported me for 'privacy violations' because I filmed a guard, and YouTube took my video down," Guan recalled.

He was forced to appeal and use YouTube's tools to blur the face. Once the video was back up, the attackers saw this tactic worked and started "mass reporting" all his videos. Guan's dashboard was instantly flooded with "violation notifications."

This precise cyber-violence, launched by the state machine, combined with the systematic technical siege, broke Guan psychologically.

" The pressure was immense," Guan recalled. "I basically stopped paying attention, actively avoided looking at it." The insane cyberbullying drove him into severe depression. To protect himself, he cut off information from the outside world. Because of this, he didn't even know until his recent arrest just how huge of an impact his video had made internationally. He only knew he was being organizedly "doxxed" by the state, and he was scared.

He went into hiding. But the real eye of the storm exploded in his hometown of Nanyang, Henan.

According to Guan and his mother, just over a month after the video release, in January 2022, a systematic "guilt by association" campaign led by state security targeted all his relatives.

"When I went back from Taiwan [in late 2023], everyone in the family was super nervous," Ms. Luo said. "They were worried I'd be detained at the airport because they'd already been interrogated."

Ms. Luo said her four sisters in Henan and Zhengzhou were summoned by local state security almost simultaneously. "The police told them," Ms. Luo said, "'If you have any news about Guan Heng, report it immediately. If you know something and don't report it, you know the consequences.'"

In late January 2022, four police officers took Guan's father from his home for an interrogation that lasted from noon until 9 PM. They confiscated his phone to "recover data" at the Nanyang City Bureau. That night, they dragged his father to Guan's grandmother's house—where he lived before leaving—seized his computer tower, and issued a "confiscation list." Over a month later (March 2022), state security interrogated his father again.

Agents also found the aunt Guan was closest to growing up. They took his aunt and uncle separately for interrogation. This psychological warfare completely broke his aunt. "She's so scared she can't sleep at night now," Ms. Luo said. "She later told Guan's father point-blank: 'Please don't come to me about Guan Heng anymore! We have to live here, I'm afraid it will affect my kids, afraid of getting implicated! Please stop harassing me!'"

Guan didn't know any of this. While he thought he was just digesting the trauma of online abuse alone in New York, his entire family back in China had been thoroughly "combed through" and terrified by state security.

And so, carrying his trauma and a complete break from his homeland, Guan lived alone in the US for three years. Until the summer of 2025, when fate pushed him into another cage in the most absurd way possible.

5. From one cage to another.

For over three years in the US, Guan Heng tried to rebuild his life in solitude. On October 25, 2021, he filed for asylum in New York, got his work permit, bought a used car, and started out driving Uber and delivering food in NYC. Later, he switched to long-haul trucking "because living in the truck meant I didn't need an apartment." When he quit trucking, he decided to move out of the city.

"I really love the state parks upstate," he said. Seeking a quieter environment closer to nature, he moved to a small town near Albany in the spring of 2025.

He was just a tenant. The house he shared was run by a Chinese couple, the "sub-landlords." His quiet life lasted until that morning in 2025, when the violent banging of ICE agents shattered the peace.

During the raid, Guan showed his work permit and asylum documents to prove his identity. But it seemed that in the enforcement logic of ICE—under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—Guan's status with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) didn't matter.

Arrested as an "illegal immigrant" solely because he entered by sea, Guan was bounced from the ICE office to a county jail, then to the Buffalo detention center, and finally to Broome County jail.

At first, he was in the immigration unit. "It was okay there," he said. "I was with other immigrants, people in the same boat. We had things to talk about, played ball and cards, it was lively."

But a month later, he was moved to a unit with American inmates—many of whom, he says, are sex offenders.

He was thrown back into total isolation. "Nothing to talk about with them," he said on the phone, sounding down. " The air in the hall is bad, makes me cough if I stay too long, so mostly I just stay alone in the yard or my cell."

It was in this extreme loneliness that he began to reflect on his life.

"I met an inmate here, another immigrant," Guan said. "She told me something that really stuck with me. She said: 'Two is always better than one.'"

That hit him hard. "I thought to myself," he reflected, "if I had family or friends with me, I might not have moved upstate, and I wouldn't have been caught. If I had a partner, my mental state would be much better."

He realized that the "lone wolf" trait that allowed him to pull off the Xinjiang feat was also his Achilles' heel right now.

"Before, I always felt like a solitary warrior, that I had to solve every problem myself," he said. "But once I really got into prison, I realized that no matter how capable I am individually, I can't do anything. I have to rely completely on outside help."

Now, he realizes he must step out of his self-imposed isolation and rely on American civil society and human rights organizations to stop US law enforcement from sending him back to China—a place he risked death to expose, and where the consequences of his return would be unthinkable.

6. Rescue across the bars, and "I did the right thing."

While Guan Heng sat in Broome County jail facing the massive risk of deportation, letters of testimony began arriving in his lawyer's hands. These letters revealed a fact Guan himself hadn't known: the footage he shot alone had become a crucial piece of the puzzle for the international community's focus on the human rights crisis in Xinjiang.

The first letter came from the very source that inspired him. The Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News (Megha Rajagopalan, Alison Killing, Christo Buschek), upon hearing of Guan's plight, co-signed a letter of support. They confirmed that the "Ground Truth" provided by Guan filled the final gap in their satellite image analysis.

"Mr. Guan provided key corroboration for our investigation at great personal risk. His courage is extraordinary... There is no other plausible reason for him to be near many of these detention sites, as they are often in remote areas... If captured, the danger he faces would increase significantly," the BFN team wrote. They noted specifically that Guan's evidence helped confirm the existence of the new prison in Dabancheng—directly puncturing the Chinese government's lie that the "re-education camps had been closed."

The letter concluded: "We believe that if Mr. Guan is returned to China, he will face immense danger. Therefore, we call on the US to grant Mr. Guan asylum and end his detention and the threat of deportation."

The second letter came from Janice M. Englehart, producer of the documentary All Static & Noise.

Guan's footage was included in this documentary about the Uyghur condition, which has been screened in New Zealand, Australia, Japan, and the UK to expose the Chinese government's abuses.

Janice stated in her support letter: "Mr. Guan risked his own safety and that of his family to provide important video evidence. This evidence corroborates satellite imagery, confirming the existence of internment camps operated by the Chinese government in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region... His efforts in 2020 supported researchers, journalists, and filmmakers, allowing them to confidently understand and broadcast what is happening in a region of China that has long been inaccessible to many Western journalists, diplomats, and visitors."

At the end of the letter, Janice was blunt: "Mr. Guan's actions are entirely in the US national interest." She warned that if deported, Guan would likely face torture or even death on charges of "espionage" or "collusion with foreign forces."

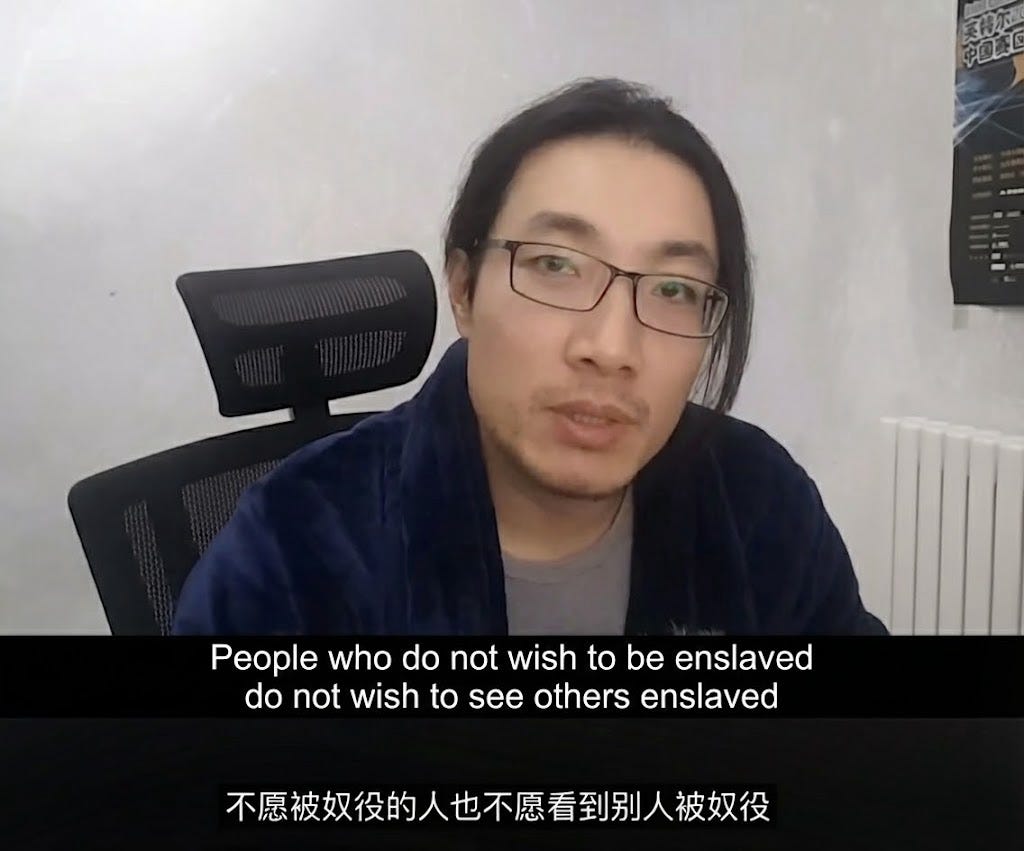

Another testimony came from Zhou Fengsuo, Executive Director of Human Rights in China. He said he noticed the young man on Twitter as early as November 17, 2021, just days after Guan arrived in the US, and reached out to him. "I thought then that he was someone acting on his conscience," Zhou recalled. But he also sensed the trauma in Guan. "He was very low-key, even evasive. Even in the US, he was living in a sort of 'hiding'."

Zhou pointed out, "This (the Uyghur issue) is a high-voltage red line for Han people. If he is sent back, given the social impact of this event, he will definitely face a very severe prison sentence." More importantly, Zhou believes Guan's ordeal reveals the common plight of many freedom seekers today: "They yearn for freedom and flee tyranny, yet live in multiple layers of fear." In his testimony, Zhou wrote, "On one hand, they have to dodge US immigration jail; on the other, they have to dodge transnational repression from the CCP."

This is the true picture of Guan Heng's last three years—surviving in the crack between "double fears," until one side finally caught him.

"America is a country built by people who love freedom," Zhou appealed in closing. "A person who loves freedom, resists tyranny, and has paid a huge price for it should be allowed to stay. He belongs in this country."

At the same time, Rushan Abbas, Executive Director of the Campaign for Uyghurs, and renowned Uyghur poet Abduweli Ayup also stepped forward to voice support for this Han man who spoke up for their people.

"If he gets sent back, he's truly dead meat." On November 10, 2025, Guan's mother, Ms. Luo, said trembling in an interview. Now in Taiwan, she is terrified for her son. Her biggest wish is for the US court to make a just ruling, stop the ICE deportation process, and let her son stay in the US. At least then, he's safe.

Ms. Luo's fear isn't baseless; similar tragedies have happened before. Young scholar Feng Siyu, a graduate of Amherst College, is a cautionary tale. She was a visiting scholar at Xinjiang University's Folklore Research Center in 2017, working with the center's director, famous anthropologist Rahile Dawut. However, Rahile was arrested in December 2017 and sentenced to life in prison the following year; Feng Siyu was also suddenly arrested in 2018 and eventually sentenced to a heavy 15 years.

Now, an effort involving Pulitzer winners, filmmakers, Uyghur leaders, and human rights activists is trying to build a "protective wall" to block ICE's deportation and get Guan his freedom back.

On October 20, 2025, in a New York state jail, wearing a prison uniform, Guan Heng waits for his December immigration hearing. When the author reached him by phone and told him his risky footage was key proof for a Pulitzer-winning report, he sounded pretty surprised.

He says he doesn't regret what he did. After going through all this, he's even more convinced that what he did was "right."

"Because I'm personally tasting what it's like to lose freedom now, I can understand even more what those people in the camps are feeling," he said on the prison phone. "I need outside help now, and they need it too. So, I still think I did the right thing."

"I feel this is a massive, unchecked, and uncontrolled evil being committed by the Chinese government," he added. "It has caused the pain of separation and loss of freedom for countless families. So, even now, I still firmly oppose everything the Chinese government is doing in Xinjiang."

But as an "illegal immigrant" stripped of his freedom, his only hope now lies in the urgent rescue efforts of lawyers, journalists, and human rights organizations on the outside.

Guan Heng in 2019

On December 15, Guan Heng's asylum case opens in New York. His fate hangs in the balance, resting on one question: Will this free world he risked everything to reach choose to protect him, or send him back to the homeland he exposed at the risk of death and fled in search of liberty and justice? view all

This is a story about guts, a getaway, and a cruel twist of irony.

In October 2020, Guan Heng, a young guy from Henan, China, drove solo deep into the heart of Xinjiang. Armed with a long-lens camera, he documented the internment facilities hidden behind the wilderness, towns, and military barracks. To get this footage out to the world, he embarked on a hair-raising escape: zigzagging through South America, and finally, piloting a small boat alone for 23 hours across the ocean, making landfall in Florida from the Bahamas. After arriving in the US in 2021, he released the videos as planned. These clips became key evidence for the international community—including the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News—to confirm what China was doing in Xinjiang.

Guan Heng thought he was safe. But four years later, he lost his freedom right here in the States. In August 2025, during an ICE raid targeting his housemates, Guan was arrested in Upstate New York for "illegal entry." Now, sitting in the Broome County Correctional Facility, he faces the threat of deportation—being forced back to the very country he risked everything to escape.

On the morning of August 21, 2025, in a residential neighborhood in Upstate New York, Guan Heng was jolted awake by a violent pounding on the door. It was ICE agents.

They weren't there for him. Their target was his roommate—a couple in the business of flipping shops who had been reported due to a financial dispute. But when the agents stormed in with a search warrant, they "bumped into" the 38-year-old Guan Heng, and he was taken into custody on the spot. The exchange went like this:

Agent: "How’d you get into the country?"

Guan: "I drove a boat over from the ocean myself."

Agent: "Do you have an I-94 form (arrival record)?"

Guan: "No."

Guan was first taken to an ICE office, then tossed in a county jail near Albany for a day. From there, he was shipped to an immigration detention center in Buffalo for nearly a week, before finally landing where he is now—Broome County Correctional Facility.

"They couldn't care less if I have a work permit or what the status of my asylum case is," Guan said, his voice thick with confusion and frustration during a phone interview with Human Rights in China in October 2025. "They only care about how I entered. They just say I didn't come through a normal customs checkpoint, so the act itself is illegal."

His pending asylum interview, his legal work permit, his New York State driver's license... in the eyes of ICE, all of it was worth zilch compared to the fact of his "Entry Without Inspection."

With the Trump administration cracking down hard on illegal immigration, the Broome County jail is packed to the gills. Months have passed, and Guan waits for the outcome of his case in a state of anxiety and depression. Nobody there knows what this young man from China went through over the past few years; nobody knows that the footage he risked his life to shoot provided crucial corroboration of the Chinese authorities' actions against the Uyghurs. And nobody knows the immense danger he faces if he gets sent back.

1. "I wanted to go to Xinjiang and see for myself what was really going on."

Guan Heng calls Nanyang, Henan his home. He was born in November 1987.

According to Guan and his mother, his parents divorced when he was young, and he was raised by his grandmother. After she passed, he’s been on his own. Before leaving China in July 2021, he worked a bunch of different gigs—ran a fast-food joint, worked in the oil fields for a few years, and later freelanced. By his own account, he learned how to "jump the Great Firewall" (bypass internet censorship) pretty early on.

Unlike many young Chinese people, Guan didn't just use the VPN to watch movies or listen to music. He used the internet to touch the "forbidden zones" buried by official narratives: from the Great Famine of the 1960s to the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989. This raw information from the outside world hit him hard, cracking his worldview wide open.

"I learned bit by bit, and finally realized that the Chinese government was hiding so many dirty secrets," he recalled in a jailhouse phone interview with the author in November 2025. He said that since graduating college, he had become a silent dissident—someone living under the regime, but whose mind had already "broken out of prison."

In 2019, Guan rode a motorcycle from Shanghai all the way to Xinjiang as an adventure tourist. He thought it would be a scenic road trip, but he slammed into an invisible wall of high-pressure control.

" The vibe was obvious," he said. "As soon as you enter Xinjiang, there are checkpoints everywhere, police and armed guards all over the place. Even checking into a hotel requires repeated registration and facial recognition." At gas stations, he faced strict restrictions just for being on a motorcycle. This trip gave him a firsthand look at the government's harsh social management system in the region, though he didn't fully understand the depth of it at the time.

In 2020, when COVID hit, Guan was locked down at home like hundreds of millions of other Chinese people. Bored out of his mind surfing the web, he clicked on a report from the famous American outlet BuzzFeed News (BFN). The report used satellite imagery and data to reveal a massive network of concentration camps spread across Xinjiang.

In that moment, the questions from his 2019 trip were answered. He realized those checkpoints, police, and facial recognition systems he saw were actually the outer perimeter of this massive surveillance state.

"Knowing the Chinese government, they love covering up stuff they don't want people to see," Guan said. "It really piqued my interest, especially since I'd been there and knew nothing about it. I immediately wanted to go back and see with my own eyes what the hell was going on."

He knew perfectly well that for a regular guy to do this as a tourist was basically a "suicide mission." "I fully expected the risks," he said calmly. He started prepping like he was planning a covert op: instead of his own pro gear, he rented a long-range DV camcorder online so he could film from a safe distance.

He prepped two SD cards. One for filming, which he’d hide in a secret spot in the car immediately after shooting; and a dummy card to stick back in the camera. "I was afraid of getting stopped and searched," he said. "At least they wouldn't know what I'd filmed."

In October 2020, Guan Heng drove alone toward the trouble spot he’d visited a year prior—Xinjiang.

2. "Roaming" Xinjiang for three days: Verifying prison coordinates one by one.

Guan's trip wasn't an aimless wander; it was a treasure hunt based on a map. That "map" consisted of satellite coordinates marked as suspected "detention camps" in the BuzzFeed News report.

He spent three whole days crisscrossing the vast lands of Xinjiang, fact-checking the coordinates marked as gray (low confidence), yellow (medium confidence), and red (high confidence).

His first stop was Hami City. Before hitting the city, he went to a place called "Beicun," marked with a gray tag. It was a pink building, no barbed wire, didn't look like anyone was there—didn't look like a prison.

Next, he drove into downtown Hami and found a yellow marker. The sign out front read "Hami Compulsory Drug Rehabilitation Center." It was in a busy area with heavy traffic, which made Guan skeptical. "A rehab center in a busy downtown isn't likely to be a detention camp." But right after that, he found another yellow marker—"Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps 13th Division Detention Center."

This place immediately put him on edge. It was tucked at the end of a small alley. Not only did the detention center itself have towering walls, but several adjacent courtyards were also ringed with high walls and barbed wire—definitely not normal residential compounds. This matched the description of the concentration camps perfectly.

To cover his tracks, Guan bought some snacks at a shop at the alley entrance on his way out and "deliberately" paid with WeChat. "If I got questioned," he explained later, "at least I’d have an excuse for why I was in that dead-end alley."

The second day, Guan was on the road constantly. He passed through three counties: Mulei, Jimsar, and Fukang. He found that many of the BFN markers pointed to existing "detention centers" or "jails"—Mulei County Detention Center, Jimsar County Detention Center, Fukang City Detention Center. In Mulei, he found two gray markers: a "Farmers and Herdsmen Training School" and a "Vocational Education Center." Although the buildings looked abandoned, the barbed wire still on the walls seemed to whisper of their former use.

That day's journey made him realize the scale of the campaign was far bigger than he imagined—the authorities weren't just building new facilities; they were utilizing, retrofitting, and expanding the entire existing incarceration system.

However, this was tricky. Watchtowers and barbed wire are standard for jails, so judging by appearance alone, it was hard to tell if they were being used as concentration camps for Uyghurs.

On the third day, Guan drove through three cities: Urumqi, Dabancheng, and Korla. This was his most productive—and most dangerous—day.

In the suburbs of Urumqi, following the coordinates, he found the "Urumqi No. 2 Education and Correction Bureau (Drug Rehab Center)." He parked far away, posed as a jogger out for a morning run, and filmed with a GoPro as he walked. He not only captured the rehab center but also discovered three other heavily guarded compounds nearby. At the gate of one facility, he filmed a vegetable truck unloading—proof the facility was active.

Right after, at a place nearby called "Gaoke Road," he made his key discovery. On one side of the road lay a sprawling complex of huge facilities, complete with high walls and watchtowers, yet it wasn't marked on any map. Guan zoomed in with his long lens and successfully captured the bold red characters on the roof: "Reform through Labor, Reform through Culture."

That afternoon, he headed to Dabancheng. This was a "red marker," hidden deep in the wilderness far from the highway, without even a gravel road leading to it. Guan parked by a pond and climbed a high dirt mound alone.

"I was nothing but nervous," he recalled. Lying flat on the mound, his lens filled with a brand-new, massive, but seemingly unopened facility. He snapped his shots and hurried down, breaking into a cold sweat—he realized there was actually a house on top of the hill he’d just climbed, and down by the pond where he parked, a fisherman had appeared out of nowhere.

Forcing himself to stay calm, he walked up to the guy. "Hey boss, catch anything?" After confirming the guy hadn't noticed his shady behavior, he got in his car and sped off.

The final stop was Korla, 339 kilometers from Urumqi. Here, the coordinates pointed behind a military base (there were tanks at the gate). It was a massive, heavily guarded facility, and the only way in was through the military camp.

As Guan tried to pull off onto the shoulder to get a shot, someone from a shop next to the base walked out and stared him down, dead in the eyes.

In the tension of the standoff, Guan thought fast. He slammed on the gas, drifting his high-chassis SUV in the dirt, spinning donuts, deliberately acting like a guy just testing out his car's performance. The "shopkeeper" seemed confused by this crazy driver, watched for a bit, and then boredly went back inside.

The second the guy turned around, Guan stopped, whipped out his long-lens DV, and captured the final scene of his video.

3. Drifting at sea for a day and a night: Smuggling into the US from the Bahamas.

The video was done. Guan Heng possessed a "digital bomb," but he quickly realized a fatal problem: he couldn't hit the "publish" button without blowing himself up.

"I knew, finishing the video was one thing, but once it hit the internet, the police would definitely find me," Guan said in the interview. "If they got to me, the videos would either never get out or be deleted, and my life would be in danger."

The only way out he could think of was to leave China first.

But the fuse on this bomb was stretched painfully long. Since the outbreak in 2020, China's borders had been sealed. Guan had nowhere to go, sitting on this footage in depression and anxiety. Finally, in the summer of 2021, a window opened. On July 4, he left via Shekou, departed from Hong Kong, and flew to Ecuador, a South American country that was visa-free for Chinese passports at the time.

He stayed in Ecuador for over two months for one reason: to get the Pfizer vaccine. He didn't trust the Chinese domestic vaccines, but the policy back home was getting stricter—"No vax meant a red health code, you couldn't go anywhere."

After two shots, he flew to another visa-free country—The Bahamas. Here, he was separated from his final destination by just a strip of water. He wanted to buy a boat from China and have it shipped to save money, but his Bahamian visa was ticking away—he recalls only having 14 days—and logistics were slow. By October 2021, he couldn't wait any longer. He spent his last $3,000 at a local marine supply store on a small inflatable boat and an outboard motor. He launched from Freeport, Bahamas, aiming for Florida. Google Maps said it was about 85 miles as the crow flies.

According to Guan, he had zero nautical experience, didn't know how to row, and got seasick easily. This was his first time "captaining" a vessel. His only tools were a mechanical compass and a phone with offline GPS maps.

"I was drifting on the ocean for nearly 23 hours," he recalled. He brought plenty of food and water, but was so nervous he "only drank one can of Coke the whole time." The biggest threat wasn't the waves, but his sketchy engine.

"I didn't have much money, so I didn't buy a closed fuel tank," he said. "I had to hold a gas can and pour fuel directly into the engine while the boat was rocking violently." Gasoline spilled everywhere, filling the dinghy with heavy fumes, ready to explode at the slightest spark.

"That boat turned into a floating bomb," Guan said. "I was actually terrified, because if it caught fire, I'd never make it to America."

He planned to land at night to avoid detection. But in the endless drifting, his only thought was "just get there."

The next morning, he saw the Florida coastline in the distance. Around 9 AM, the boat hit the sand. There were already tourists taking morning walks on the beach, and an elderly couple was walking toward him. Guan's heart was in his throat, terrified they would call the cops.

Ignoring the boat and his scattered luggage, he grabbed his most important backpack. The moment the boat hit the shallows, he jumped off and sprinted into the coastal bushes. Hiding in the brush, gasping for air, he watched a Coast Guard patrol boat cruise by just offshore. But he was safe.

Just like that, through smuggling, Guan Heng arrived in the "Free World" he had longed for.

4. The video shocks the web, but he and his family pay a heavy price.

According to Guan, before he launched from the Bahamas, he had already scheduled the video release. "I didn't know if I'd make it to the US alive," he said. "I couldn't wait until I arrived to publish." The video about the Xinjiang concentration camps finally went public on his YouTube channel on October 5, 2021.

The video immediately triggered a massive reaction. As rare, first-person footage from a Chinese citizen, Guan's video was quickly reported on and cited by media outlets like Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Asia. More importantly, it provided key on-the-ground proof for the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News. In interviews, BFN reporters emphasized the extraordinary value of Guan's footage, praising his courage and stating that the new information confirmed their analysis of what was happening in Xinjiang.

Meanwhile, as the one who lit the fuse, Guan himself faced pressure beyond his worst nightmares—a massive wave of attacks from Chinese state security and online propaganda trolls began immediately.

Shortly after the video dropped, a YouTuber named "Science Guy K-One Meter" posted a "doxxing" video, stripping Guan's personal info bare—real name, birthday, college, home address—everything. This "Science Guy," typically, posts pro-CCP content.

"They doxxed Guan Heng," said Ms. Luo, Guan's mother, in an interview with Human Rights in China on November 1, 2025. Her voice trembled with anger. "The comments underneath were incredibly nasty, calling him a traitor to the Han race, and saying things like 'hope he gets accidentally killed by a black brother in America'."

Simultaneously, a "siege" on his YouTube channel began. "First they reported me for 'privacy violations' because I filmed a guard, and YouTube took my video down," Guan recalled.

He was forced to appeal and use YouTube's tools to blur the face. Once the video was back up, the attackers saw this tactic worked and started "mass reporting" all his videos. Guan's dashboard was instantly flooded with "violation notifications."

This precise cyber-violence, launched by the state machine, combined with the systematic technical siege, broke Guan psychologically.

" The pressure was immense," Guan recalled. "I basically stopped paying attention, actively avoided looking at it." The insane cyberbullying drove him into severe depression. To protect himself, he cut off information from the outside world. Because of this, he didn't even know until his recent arrest just how huge of an impact his video had made internationally. He only knew he was being organizedly "doxxed" by the state, and he was scared.

He went into hiding. But the real eye of the storm exploded in his hometown of Nanyang, Henan.

According to Guan and his mother, just over a month after the video release, in January 2022, a systematic "guilt by association" campaign led by state security targeted all his relatives.

"When I went back from Taiwan [in late 2023], everyone in the family was super nervous," Ms. Luo said. "They were worried I'd be detained at the airport because they'd already been interrogated."

Ms. Luo said her four sisters in Henan and Zhengzhou were summoned by local state security almost simultaneously. "The police told them," Ms. Luo said, "'If you have any news about Guan Heng, report it immediately. If you know something and don't report it, you know the consequences.'"

In late January 2022, four police officers took Guan's father from his home for an interrogation that lasted from noon until 9 PM. They confiscated his phone to "recover data" at the Nanyang City Bureau. That night, they dragged his father to Guan's grandmother's house—where he lived before leaving—seized his computer tower, and issued a "confiscation list." Over a month later (March 2022), state security interrogated his father again.

Agents also found the aunt Guan was closest to growing up. They took his aunt and uncle separately for interrogation. This psychological warfare completely broke his aunt. "She's so scared she can't sleep at night now," Ms. Luo said. "She later told Guan's father point-blank: 'Please don't come to me about Guan Heng anymore! We have to live here, I'm afraid it will affect my kids, afraid of getting implicated! Please stop harassing me!'"

Guan didn't know any of this. While he thought he was just digesting the trauma of online abuse alone in New York, his entire family back in China had been thoroughly "combed through" and terrified by state security.

And so, carrying his trauma and a complete break from his homeland, Guan lived alone in the US for three years. Until the summer of 2025, when fate pushed him into another cage in the most absurd way possible.

5. From one cage to another.

For over three years in the US, Guan Heng tried to rebuild his life in solitude. On October 25, 2021, he filed for asylum in New York, got his work permit, bought a used car, and started out driving Uber and delivering food in NYC. Later, he switched to long-haul trucking "because living in the truck meant I didn't need an apartment." When he quit trucking, he decided to move out of the city.

"I really love the state parks upstate," he said. Seeking a quieter environment closer to nature, he moved to a small town near Albany in the spring of 2025.

He was just a tenant. The house he shared was run by a Chinese couple, the "sub-landlords." His quiet life lasted until that morning in 2025, when the violent banging of ICE agents shattered the peace.

During the raid, Guan showed his work permit and asylum documents to prove his identity. But it seemed that in the enforcement logic of ICE—under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—Guan's status with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) didn't matter.

Arrested as an "illegal immigrant" solely because he entered by sea, Guan was bounced from the ICE office to a county jail, then to the Buffalo detention center, and finally to Broome County jail.

At first, he was in the immigration unit. "It was okay there," he said. "I was with other immigrants, people in the same boat. We had things to talk about, played ball and cards, it was lively."

But a month later, he was moved to a unit with American inmates—many of whom, he says, are sex offenders.

He was thrown back into total isolation. "Nothing to talk about with them," he said on the phone, sounding down. " The air in the hall is bad, makes me cough if I stay too long, so mostly I just stay alone in the yard or my cell."

It was in this extreme loneliness that he began to reflect on his life.

"I met an inmate here, another immigrant," Guan said. "She told me something that really stuck with me. She said: 'Two is always better than one.'"

That hit him hard. "I thought to myself," he reflected, "if I had family or friends with me, I might not have moved upstate, and I wouldn't have been caught. If I had a partner, my mental state would be much better."

He realized that the "lone wolf" trait that allowed him to pull off the Xinjiang feat was also his Achilles' heel right now.

"Before, I always felt like a solitary warrior, that I had to solve every problem myself," he said. "But once I really got into prison, I realized that no matter how capable I am individually, I can't do anything. I have to rely completely on outside help."

Now, he realizes he must step out of his self-imposed isolation and rely on American civil society and human rights organizations to stop US law enforcement from sending him back to China—a place he risked death to expose, and where the consequences of his return would be unthinkable.

6. Rescue across the bars, and "I did the right thing."

While Guan Heng sat in Broome County jail facing the massive risk of deportation, letters of testimony began arriving in his lawyer's hands. These letters revealed a fact Guan himself hadn't known: the footage he shot alone had become a crucial piece of the puzzle for the international community's focus on the human rights crisis in Xinjiang.

The first letter came from the very source that inspired him. The Pulitzer Prize-winning team at BuzzFeed News (Megha Rajagopalan, Alison Killing, Christo Buschek), upon hearing of Guan's plight, co-signed a letter of support. They confirmed that the "Ground Truth" provided by Guan filled the final gap in their satellite image analysis.

"Mr. Guan provided key corroboration for our investigation at great personal risk. His courage is extraordinary... There is no other plausible reason for him to be near many of these detention sites, as they are often in remote areas... If captured, the danger he faces would increase significantly," the BFN team wrote. They noted specifically that Guan's evidence helped confirm the existence of the new prison in Dabancheng—directly puncturing the Chinese government's lie that the "re-education camps had been closed."

The letter concluded: "We believe that if Mr. Guan is returned to China, he will face immense danger. Therefore, we call on the US to grant Mr. Guan asylum and end his detention and the threat of deportation."

The second letter came from Janice M. Englehart, producer of the documentary All Static & Noise.

Guan's footage was included in this documentary about the Uyghur condition, which has been screened in New Zealand, Australia, Japan, and the UK to expose the Chinese government's abuses.

Janice stated in her support letter: "Mr. Guan risked his own safety and that of his family to provide important video evidence. This evidence corroborates satellite imagery, confirming the existence of internment camps operated by the Chinese government in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region... His efforts in 2020 supported researchers, journalists, and filmmakers, allowing them to confidently understand and broadcast what is happening in a region of China that has long been inaccessible to many Western journalists, diplomats, and visitors."

At the end of the letter, Janice was blunt: "Mr. Guan's actions are entirely in the US national interest." She warned that if deported, Guan would likely face torture or even death on charges of "espionage" or "collusion with foreign forces."

Another testimony came from Zhou Fengsuo, Executive Director of Human Rights in China. He said he noticed the young man on Twitter as early as November 17, 2021, just days after Guan arrived in the US, and reached out to him. "I thought then that he was someone acting on his conscience," Zhou recalled. But he also sensed the trauma in Guan. "He was very low-key, even evasive. Even in the US, he was living in a sort of 'hiding'."

Zhou pointed out, "This (the Uyghur issue) is a high-voltage red line for Han people. If he is sent back, given the social impact of this event, he will definitely face a very severe prison sentence." More importantly, Zhou believes Guan's ordeal reveals the common plight of many freedom seekers today: "They yearn for freedom and flee tyranny, yet live in multiple layers of fear." In his testimony, Zhou wrote, "On one hand, they have to dodge US immigration jail; on the other, they have to dodge transnational repression from the CCP."

This is the true picture of Guan Heng's last three years—surviving in the crack between "double fears," until one side finally caught him.

"America is a country built by people who love freedom," Zhou appealed in closing. "A person who loves freedom, resists tyranny, and has paid a huge price for it should be allowed to stay. He belongs in this country."

At the same time, Rushan Abbas, Executive Director of the Campaign for Uyghurs, and renowned Uyghur poet Abduweli Ayup also stepped forward to voice support for this Han man who spoke up for their people.

"If he gets sent back, he's truly dead meat." On November 10, 2025, Guan's mother, Ms. Luo, said trembling in an interview. Now in Taiwan, she is terrified for her son. Her biggest wish is for the US court to make a just ruling, stop the ICE deportation process, and let her son stay in the US. At least then, he's safe.

Ms. Luo's fear isn't baseless; similar tragedies have happened before. Young scholar Feng Siyu, a graduate of Amherst College, is a cautionary tale. She was a visiting scholar at Xinjiang University's Folklore Research Center in 2017, working with the center's director, famous anthropologist Rahile Dawut. However, Rahile was arrested in December 2017 and sentenced to life in prison the following year; Feng Siyu was also suddenly arrested in 2018 and eventually sentenced to a heavy 15 years.

Now, an effort involving Pulitzer winners, filmmakers, Uyghur leaders, and human rights activists is trying to build a "protective wall" to block ICE's deportation and get Guan his freedom back.

On October 20, 2025, in a New York state jail, wearing a prison uniform, Guan Heng waits for his December immigration hearing. When the author reached him by phone and told him his risky footage was key proof for a Pulitzer-winning report, he sounded pretty surprised.

He says he doesn't regret what he did. After going through all this, he's even more convinced that what he did was "right."

"Because I'm personally tasting what it's like to lose freedom now, I can understand even more what those people in the camps are feeling," he said on the prison phone. "I need outside help now, and they need it too. So, I still think I did the right thing."

"I feel this is a massive, unchecked, and uncontrolled evil being committed by the Chinese government," he added. "It has caused the pain of separation and loss of freedom for countless families. So, even now, I still firmly oppose everything the Chinese government is doing in Xinjiang."

But as an "illegal immigrant" stripped of his freedom, his only hope now lies in the urgent rescue efforts of lawyers, journalists, and human rights organizations on the outside.

Guan Heng in 2019

On December 15, Guan Heng's asylum case opens in New York. His fate hangs in the balance, resting on one question: Will this free world he risked everything to reach choose to protect him, or send him back to the homeland he exposed at the risk of death and fled in search of liberty and justice?

The Chinese government has begun to compel the display of portraits of Chinese political figures inside the Mosques (Masajid)

News • napio posted the article • 0 comments • 225 views • 2025-10-29 01:46

The Chinese government has begun to mandate the display of portraits of Chinese political figures inside the Mosques (Masajid)

The translated content in these two images:

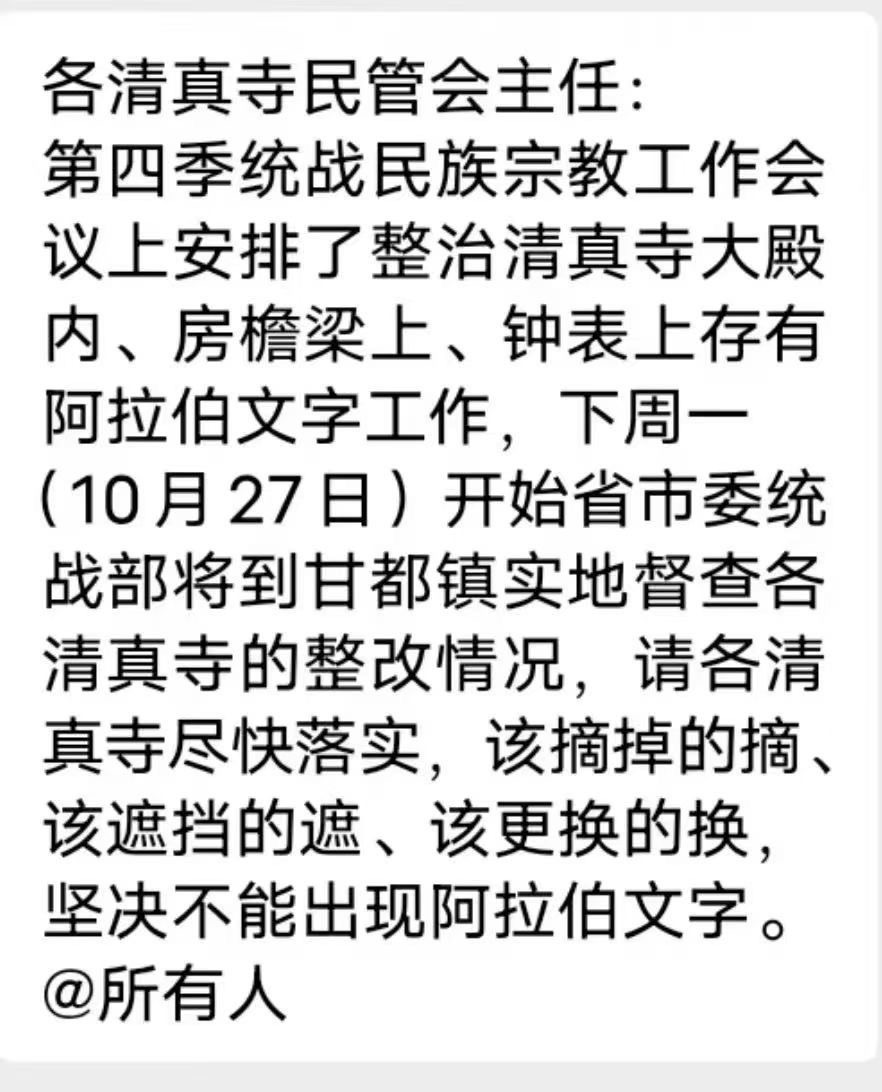

To all Chairmen of the Mosque Management Committees (Majlis):

At the Fourth Quarter United Front Work Department meeting on ethnic and religious affairs, arrangements were made to rectify (tashih) the presence of Arabic script (or Al-Kitabat al-Arabiyyah) inside the main prayer hall (Musalla), on the eaves and beams, and on the clocks of our Mosques (Masajid).

Starting next Monday, October 27th, the United Front Work Departments of the Provincial and Municipal Committees will be conducting on-site supervision in Gandu Town, Qinghai province, China. to check the rectification status of all Mosques.

I urge all Mosques to implement these changes immediately. What needs to be taken down, take it down; what needs to be covered, cover it; and what needs to be replaced, replace it. There must be absolutely no visible Arabic script (Kalam Allah).

@Everyone

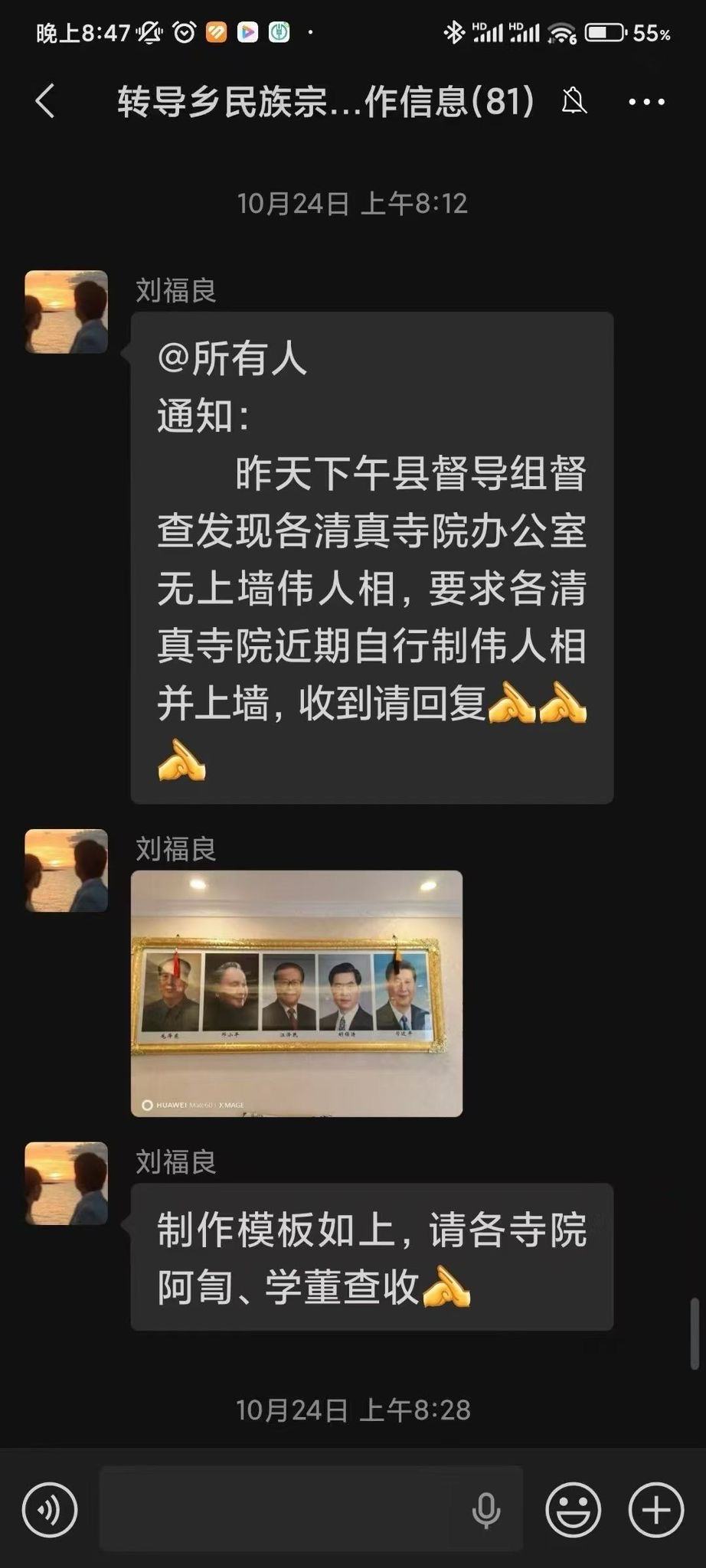

Forwarding Information from the Township Ethnic and Religious Affairs... Working Group (81)

8:12 AM, October 24th

Liu Fuliang @Everyone - Notice:

The County Supervision Group inspected yesterday afternoon and found that there were no portraits of the Great Leaders (Zu'ama' al-A'zham) displayed on the walls of the Mosque offices.

All Mosques are now required to print and mount the Leaders' portraits on the walls themselves in the near future. Please reply to confirm receipt. view all

The Chinese government has begun to mandate the display of portraits of Chinese political figures inside the Mosques (Masajid)

The translated content in these two images:

To all Chairmen of the Mosque Management Committees (Majlis):

At the Fourth Quarter United Front Work Department meeting on ethnic and religious affairs, arrangements were made to rectify (tashih) the presence of Arabic script (or Al-Kitabat al-Arabiyyah) inside the main prayer hall (Musalla), on the eaves and beams, and on the clocks of our Mosques (Masajid).

Starting next Monday, October 27th, the United Front Work Departments of the Provincial and Municipal Committees will be conducting on-site supervision in Gandu Town, Qinghai province, China. to check the rectification status of all Mosques.

I urge all Mosques to implement these changes immediately. What needs to be taken down, take it down; what needs to be covered, cover it; and what needs to be replaced, replace it. There must be absolutely no visible Arabic script (Kalam Allah).

@Everyone

Forwarding Information from the Township Ethnic and Religious Affairs... Working Group (81)

8:12 AM, October 24th

Liu Fuliang @Everyone - Notice:

The County Supervision Group inspected yesterday afternoon and found that there were no portraits of the Great Leaders (Zu'ama' al-A'zham) displayed on the walls of the Mosque offices.

All Mosques are now required to print and mount the Leaders' portraits on the walls themselves in the near future. Please reply to confirm receipt.

The Beijing Education Commission has issued a decree to completely remove "Halal" and "Hui" labels from school canteens, and to ban the use of any religious or ethnic elements.

News • napio posted the article • 0 comments • 224 views • 2025-10-29 01:22

• This is not mere "secularization," as some might call it; rather, it is a blatant policy of assimilation (or, in Arabic, tahawwul).

• 1: It prevents minority groups from openly expressing their dietary culture and their way of life (sunnah).

• 2: It is a complete erasure of the term Halal (the Divinely permissible) from the canteens, dining tables, and the entire campus environment.

• 3: It compels our Hui Muslim students to lose their separate space for their religious diet (Tayyib and Halal) by forcing them into a "mixed dining" arrangement.

• Internal Document (or: Confidential).

• The Beijing Municipal Education Commission (BMEC).

• Notice on Carrying out an Inspection, Investigation, and Rectification of School Canteens Involving Ethnic and Religious Matters.

• To the Education Committees of all Districts, Yanshan Education Committee, Social Affairs Bureau of the Economic Development Zone, all Universities and Colleges, all Secondary Vocational Schools, and all Directly-Affiliated Schools:

• Recently, some isolated localities and schools across the country have faced issues regarding the management of on-campus dining for ethnic minority teachers and students who observe Halal dietary practices, leading to some public controversy and media attention.

• Based on the requirements of relevant directives, and in order to ensure sound ethnic and religious work in schools, proactively resolve potential risks related to ethnic and religious issues in the education sector, and prevent the over-generalization (or "abuse") of the Halal concept, we are hereby issuing this notice regarding the inspection and rectification of issues in Halal canteen management:

I. Manifestation of Issues

• First, connecting the Halal diet exclusively to a specific ethnicity and simply labeling canteens as "Hui Canteens."

• Second, failing to consider the actual proportion of students in the school, and instead either exclusively running a Halal canteen or solely providing Halal meals.

• Third, using inappropriate language in canteen publicity materials, bidding announcements, and other procedures, which highlights religious factors like Halal or "Hui ethnicity."

II. Scope of Inspection

• A comprehensive investigation is to be launched across all types and levels of schools throughout the city to ascertain the complete situation, leaving no blind spots.

III. Principles for Rectification of Identified Issues

• First, Respect for Customs. This means respecting the customs and traditions of ethnic minorities and fulfilling the normal meal requirements of ethnic minority teachers and students who observe the Halal diet.

• In schools where Hui (Muslim) and other ethnic minority teachers and students are relatively concentrated, we should not impose a one-size-fits-all approach by providing only Halal meals. Instead, we must diversify the meal options through multiple channels to satisfy the dining needs of all ethnic groups, and promote mixed dining.

• Second, Accurate Definition. We must define and manage Halal food from the perspective of ethnic minority customs, strictly limiting Halal food to only those items containing animal meat or its derivatives.

• This must not be defined by Islamic religious law (Shari'ah). Food items that do not contain meat, animal fats, or dairy ingredients are not allowed to be labeled with the term "Halal."

• Third, Halal dining must not be tied to a specific ethnicity, and canteens should not be simply named "Hui Canteen" or similar.

• Fourth, for any current labeling such as Halal (Hui) Canteen, Hui (Muslim) Meal Counter, Halal (Hui) Cooking Area, or any other signs bearing the terms Halal or Hui, and any Islamic symbols (Shu'ur Islamiya), the school canteens must be thoroughly purged of these religious markers. These can be adjusted to be named Local (Ethnic) Restaurant, Local (Ethnic) Flavor Counter, or similar.

IV. Work Requirements

• First, Pay Attention to Methods. The inspection and rectification work is quite sensitive, so during the process, we must focus on the methods used, adhere to a cautious and stable approach, ensure meticulous planning and comprehensive coordination. We must adopt the principle of 'Do More, Say Less,' and 'Act, Don't Talk,' to prevent public controversy.

• Second, Ensure Harmony and Stability. All districts must strengthen policy guidance for key schools, and all units must genuinely engage in ideological work with teachers, students, and parents. We must use the summer break to actively and prudently advance the rectification to ensure harmony and stability.

• Third, Strict Deadlines. All units are requested to report the inspection results and the corresponding rectification of any issues (see Appendices 1 and 2) to the Commission via email by July 18th.

• The email subject line must specify "** School Canteen Inspection" or "** District Canteen Inspection," to be sent to the email address [email protected]. All district education committees must compile the information by district and then submit it to the Commission.

• Contact Person: Chang Yong (Higher Education) 55530245

• Zou Xiang (Primary and Secondary Schools) 55530249

• Cao Tiange (Information Submission) 1811570681

• Appendix: 1. Inspection Report Form (Primary and Secondary Schools)

1. Inspection Report Form (Higher Education)

• Beijing Municipal Education Commission

• July 15, 2025

view all

• This is not mere "secularization," as some might call it; rather, it is a blatant policy of assimilation (or, in Arabic, tahawwul).

• 1: It prevents minority groups from openly expressing their dietary culture and their way of life (sunnah).

• 2: It is a complete erasure of the term Halal (the Divinely permissible) from the canteens, dining tables, and the entire campus environment.

• 3: It compels our Hui Muslim students to lose their separate space for their religious diet (Tayyib and Halal) by forcing them into a "mixed dining" arrangement.

• Internal Document (or: Confidential).

• The Beijing Municipal Education Commission (BMEC).

• Notice on Carrying out an Inspection, Investigation, and Rectification of School Canteens Involving Ethnic and Religious Matters.

• To the Education Committees of all Districts, Yanshan Education Committee, Social Affairs Bureau of the Economic Development Zone, all Universities and Colleges, all Secondary Vocational Schools, and all Directly-Affiliated Schools:

• Recently, some isolated localities and schools across the country have faced issues regarding the management of on-campus dining for ethnic minority teachers and students who observe Halal dietary practices, leading to some public controversy and media attention.

• Based on the requirements of relevant directives, and in order to ensure sound ethnic and religious work in schools, proactively resolve potential risks related to ethnic and religious issues in the education sector, and prevent the over-generalization (or "abuse") of the Halal concept, we are hereby issuing this notice regarding the inspection and rectification of issues in Halal canteen management:

I. Manifestation of Issues

• First, connecting the Halal diet exclusively to a specific ethnicity and simply labeling canteens as "Hui Canteens."

• Second, failing to consider the actual proportion of students in the school, and instead either exclusively running a Halal canteen or solely providing Halal meals.

• Third, using inappropriate language in canteen publicity materials, bidding announcements, and other procedures, which highlights religious factors like Halal or "Hui ethnicity."

II. Scope of Inspection

• A comprehensive investigation is to be launched across all types and levels of schools throughout the city to ascertain the complete situation, leaving no blind spots.

III. Principles for Rectification of Identified Issues

• First, Respect for Customs. This means respecting the customs and traditions of ethnic minorities and fulfilling the normal meal requirements of ethnic minority teachers and students who observe the Halal diet.

• In schools where Hui (Muslim) and other ethnic minority teachers and students are relatively concentrated, we should not impose a one-size-fits-all approach by providing only Halal meals. Instead, we must diversify the meal options through multiple channels to satisfy the dining needs of all ethnic groups, and promote mixed dining.

• Second, Accurate Definition. We must define and manage Halal food from the perspective of ethnic minority customs, strictly limiting Halal food to only those items containing animal meat or its derivatives.

• This must not be defined by Islamic religious law (Shari'ah). Food items that do not contain meat, animal fats, or dairy ingredients are not allowed to be labeled with the term "Halal."

• Third, Halal dining must not be tied to a specific ethnicity, and canteens should not be simply named "Hui Canteen" or similar.

• Fourth, for any current labeling such as Halal (Hui) Canteen, Hui (Muslim) Meal Counter, Halal (Hui) Cooking Area, or any other signs bearing the terms Halal or Hui, and any Islamic symbols (Shu'ur Islamiya), the school canteens must be thoroughly purged of these religious markers. These can be adjusted to be named Local (Ethnic) Restaurant, Local (Ethnic) Flavor Counter, or similar.

IV. Work Requirements

• First, Pay Attention to Methods. The inspection and rectification work is quite sensitive, so during the process, we must focus on the methods used, adhere to a cautious and stable approach, ensure meticulous planning and comprehensive coordination. We must adopt the principle of 'Do More, Say Less,' and 'Act, Don't Talk,' to prevent public controversy.

• Second, Ensure Harmony and Stability. All districts must strengthen policy guidance for key schools, and all units must genuinely engage in ideological work with teachers, students, and parents. We must use the summer break to actively and prudently advance the rectification to ensure harmony and stability.

• Third, Strict Deadlines. All units are requested to report the inspection results and the corresponding rectification of any issues (see Appendices 1 and 2) to the Commission via email by July 18th.

• The email subject line must specify "** School Canteen Inspection" or "** District Canteen Inspection," to be sent to the email address [email protected]. All district education committees must compile the information by district and then submit it to the Commission.

• Contact Person: Chang Yong (Higher Education) 55530245

• Zou Xiang (Primary and Secondary Schools) 55530249

• Cao Tiange (Information Submission) 1811570681

• Appendix: 1. Inspection Report Form (Primary and Secondary Schools)

1. Inspection Report Form (Higher Education)

• Beijing Municipal Education Commission

• July 15, 2025

In the saline-alkali land (mainland China), the Hui People have already completely lost their religious freedom.

Articles • ahmedla posted the article • 0 comments • 277 views • 2025-10-06 08:27

When a person spends a long time in a place without freedom, like a mental institution or a prison, they lose their independence and develop deficiencies in their ability to survive in society.

This is the sickness of institutionalization.

People who are institutionalized for a long time develop mental health problems and become dependent on the very system that harms them.

They think they are trying to survive, but in reality, they are on a path to extinction.

The reason the Huimin have been able to survive in the saline-alkali land (mainland China) until today is mainly due to a kind of cultural independence, not the sort of localized adaptation that academics often discuss.

In fertile soil, adaptation might be a good thing.

But in the saline-alkali land (mainland China), where the flower of civilization cannot blossom, adaptation will lead to one's own demise.

Therefore, the great scholar Hu Dengzhou established the Jingtang (madrasah) education, rejecting the socialization of the saline-alkali land, setting up his own schools, and using the bestowing of robes and certificates as the standard for recognizing an ahong's qualifications.

And the Huimin mosque communities would only hire ahongs who were certified according to this standard.

Regarding the authority to certify an ahong, it comes from the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) authorizing his disciples to carry on his sacred mission. In the context of the Huimin's Jingtang education, this was ritualized when a senior teacher would wrap a turban and bestow robes on his student to grant him the qualification of an ahong and the authority to begin teaching.

This authority to certify ahongs is both a matter of religious freedom and a right of a minority group.

The United Nations human rights covenants state: "In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language."

The governments of all signatory countries have a human rights obligation in this regard.

The Huimin should rightfully defend this right of theirs.

For the Huimin to maintain their cultural independence, the most important thing is freedom.

In education, they need the autonomy to run their own schools; for an ahong's qualification, they need certification by a senior teacher according to the master-disciple tradition; and for an ahong's appointment, they need the democratic choice of the mosque community.

—All of these must exclude the interference of secular authority.

If the Huimin could have freedom in these areas, even if they cannot realize the grand vision of spreading Islam in China, they would not perish.

But now, the authorities are systematically squeezing this space for freedom.

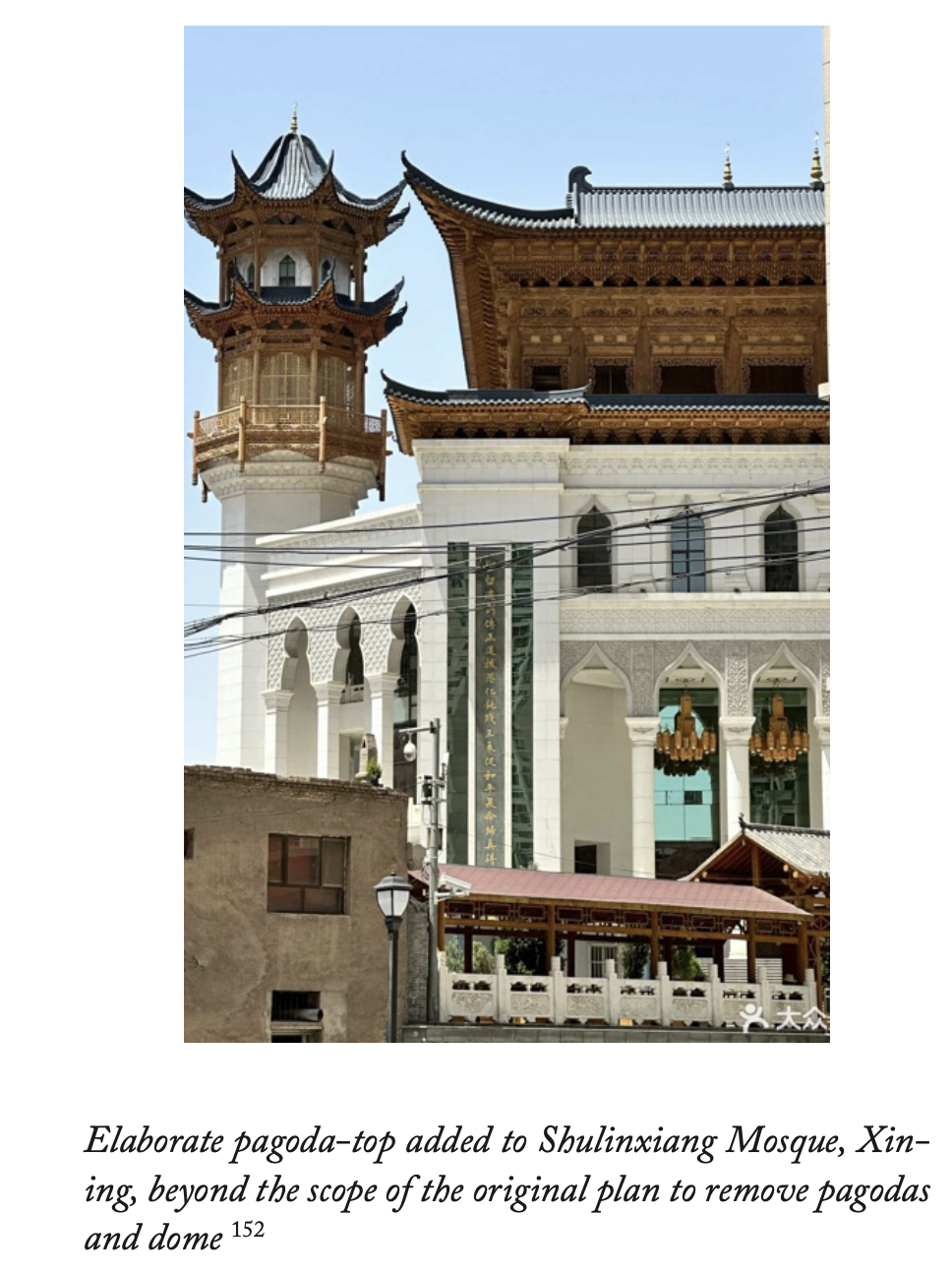

The most vivid aspect of this squeezing of freedom is none other than the architectural imprints expressing official ideology that are forcibly added to destroyed mosques.

It tells the Huimin that they have penetrated the most central areas of their community life.

The Huimin see it every day and deeply feel its expression of power.

The Huimin have lost the freedom to express their architectural culture in this land.

And the freedom of publication and freedom of speech have also long been lost.

The state-run Islamic institutes and ahong certificates further strip freedom from Huimin society.

When the Huimin completely lose the freedom of cultural education and ahong certification, that will be the moment their spirit withers and dies, both as an ethnic group and as a religious community.

The Huimin must understand that the official ideology is incompatible with religion.

Leaving aside the few so-called "left-leaning" special periods, let's look at Document 19, which represents the era of reform and opening up; it also states—"In the history of humanity, religion is ultimately bound to disappear; however, it will only disappear naturally after the long-term development of socialism and communism, when all the objective conditions are in place."

"The figures from religious colleges are to create a corps of young religious professionals who politically love the motherland, support the Party's leadership and the socialist system, and also have considerable religious knowledge."

"The only correct and fundamental way to solve the religious problem can only be, under the premise of guaranteeing freedom of religious belief, to gradually eliminate the social and cognitive roots of religion's existence through the gradual development of socialist material and spiritual civilization."